Nouvelles

International Days Festival 2022 – The Suceava Interviews - by Nick Awde

The Matei Vișniec Theatre’s International Days Festival in Suceava, Romania – seven reactions to this year’s theme of ‘Refreshing Memory’

Who: Across a ‘cluster article’, all on this page, there are interviews with critic Claudiu Groza, artistic director Petru Hadârcă, art activists Luana Popa & Dumitru Dinel Teodorescu, actor Răzvan Bănuț, critic Daniela Șilindean and playwright Matei Vișniec starting and ending the cluster cycle. Cunningly, Nick Awde, a critic, has asked other critics for their opinions on the shows.

What/Where: High up in the hills of northeast Romania, just over the border from Ukraine and Moldova, the Matei Vișniec Theatre, managed by Angela Zarojanu, holds its International Days Festival each year in Suceava (pronounced ‘SooCHAHvah’). It’s a unique gathering that mixes performances of international shows with talks and debates on issues affecting society, particularly post-communist Europe – reflected in this year’s festival theme of ‘Refreshing Memory’.

When: May 2022

Web: www.teatrulmateivisniec.ro

Photos by Amedeia Vițega.

IF READ TOGETHER, THIS IS A LONG READ

Matei Vișniec – One

Playwright

Web: www.visniec.com/home.html

[Translated from Romanian & French by Nick Awde]

Nick Awde: Let’s first set the scene with your introduction from the 2022 festival programme:

“In its unique way, theatre is an instrument of transmission, from one generation to another, of humanistic ideals and critical spirit – and so it becomes a place to learn, a space of further education. Sometimes when they see a play, young people can discover shocking pages from the past, as well as learn that the history textbooks are filled with ‘forgetfulness’. For many reasons, therefore, the focus of this year’s festival is on memory, on the need to critically examine the past in order to understand who we are in the present and what might await us in the future.”

NA: That’s an impressive summing up of what theatre can do. Why is it even more urgent now?

Matei Vișniec: We need to refresh our memories for the simple reason that we are beginning to forget. The generations who have not lived through communism need to hear the memories of the generations who have lived through commuism but are beginning to forget the experience. We need to pass that on.

We are also collectively forgetting the errors of history and then repeating them. We need to remember that the reason why Putin causes such fear in every country of Eastern Europe is because he is the direct heir of Stalin. We need to remember that nazism is an interrupted process and its return along with neo-imperialism is helped by the nostalgia of many in society, so we need to remember the reality of our past.

We especially need to refresh our memories in this part of the world which is marked by the war in Ukraine. I want us to understand that Ukraine has been a victim of many empires and not just Russia – it has also been occupied by Austro-Hungary, Poland, Nazi Germany.

This reminds us how history can take once again take us to a terrible place, because Europe has passed through a long period of peace but it has forgotten how war can always return as an instrument of the ultra elites. War is something that has repeatedly destroyed Europe and yet to see another brutal war in Europe, in Ukraine, at this moment comes as an enormous shock to us.

I want us to remember all this and although theatre does not offer a complete response, what it does is to give us somewhere we can reflect together.

NA: And that’s exactly reflected in the programme, where the productions act as stepping stones for the debates and discussions.

MV: Exactly. For example, for this year’s International Days Festival, we invited two national companies from Moldova, which is an independent country but at the same time threatened by Russia – the old Soviet Union. We invited a theatre from Ukraine, from Chernivtsi, a town not far from the Romanian border. The idea is to create a regional festival, one with debates and themes strongly relevant to this part of Europe.

Romania can be considered European because it is part of the European Union and NATO. But Moldova? We want to defend it, but its secessionist Transnistra Region, which is a Russian majority-speaking area, poses a problem for the same reason that Putin demands ‘intervention’ in Mariupol and Odesa.

We are in a complex, complicated geopolitical situation here and we need to remember the past of Moldova and the Soviet Union. We are lucky that Germany was defeated and denazified after 1945 but the great fear here in Eastern Europe is Russia, because of its occupation and then its sovietisation through the decades of commnist regimes in Eastern Europe.

So that is why I suggested ‘refreshing memory’ as the festival’s theme. It frustrates me that humanity repeats its mistakes so often. Society tends to see history as a form of progress but if we don’t keep our memories, then we are shocked when the brutality of history returns. Romania and the rest of Eastern Europe want a peaceful life, we cannot find ourselves on the front line of a brutal war, a traditional one based on the carnage of massed armies clashing against each other.

Ten days of theatre allows us to explore memories here in Suceava, a town which is on the frontier near Ukraine, we are 40 kilometres from the border, and not far from Moldova.

There is a lot to get our audience thinking about memory. The Mihai Eminescu Theatre’s Siberian Files (Dosarele Siberiei) allows us to remember the gulags and the deportations from Moldova’s history in the Soviet Union. There is also their production of my play How to Explain the History of Communism to Mental Patients (Istoria comunismului povestită pentru bolnavii mintal), which is not so much a look at how communism was but more an opportunity to debate the way ideology can become a way of life, to recall how entire populations can be manipulated en masse for decades. The Matei Vișniec Theatre’s The Homecoming (Întoarcerea acasă/Le retour à la maison) is another of my plays, and this is about the return home of the dead after the fighting has ended, like a requiem that speaks of the absurdity of war.

We know that theatre cannot resolve the crises of our world, but it can help us understand the world’s dilemmas, to know that there are solutions.

Claudiu Groza

Critic at Tribuna magazine, Cluj-Napoca

Web: Tribuna Magazine

*

Nick Awde: The festival’s theme of ‘Refreshing Memory’ has a resonance for Romania not only in coming to terms with its communist past but also with Russia’s present war on Ukraine, which also threatens neighbouring Moldova. Is a theatre festival a good place to be discussing regional politics and the ideas of national identity, or should it stick to raising the bar on aesthetics?

Claudiu Groza: Theatre festivals are a good format to discuss issues in society – and in Romania we have a lot of festivals where we can do that. For instance, for seven years I curated the International New Theatre Festival, hosted at the Ioan Slavici Theatre in Arad where the focus was on the new unusual experimental rebellious type of productions, with their new aesthetics and staging – and the Festival of the Romanian Playwright in Timișoara.

Suceava’s festival does not follow a classic model. You can see that from the title – ‘International Days’. It takes the playwright Matei Vișniec and his work as its starting point and then brings in many other productions, so although the festival has a narrow focus, it has a surprising depth for the sake of the community here.

Every festival is significant and the main reason why each sets out to do what they do should be the community. We critics are specialists who see lots of shows in different places, but most people in a town or city don’t do this, and so the cultural dynamic of theatre is not accessible to them. It’s therefore important to bring to them what is happening in theatre.

Of course, you can mix it up, and there are festivals that are not so narrow, which combine experimental pieces with large audience shows, but it is the event itself that is important for the community. If the offer is larger, then everyone can choose what is good for them individually.

NA: This particular edition of International Days opens with Matei’s The Homecoming (Întoarcerea acasă/Le retour à la maison) which makes a strong statement. What do you think is the conversation that should follow?

CG: There are a lot of festivals in Romania and internationally that programme productions of plays written by Matei – because as a writer he is good at starting conversations. In Suceava this year, his play The Homecoming (Întoarcerea acasă/Le retour à la maison) is the starting point that sets that focus.

Last night on stage we saw the play make a statement for today’s reality using the motifs of dying for no reason and how the dead want to remember themselves. It explores the condition of the victim who is involved in a conflict that is not an inner personal conflict but the external drama of a soldier. Although it is not a new play, it has deeper significance because of the war in Ukraine. You understand it as a metaphor – it’s not a scholarly didactic statement but shows you how absurd is any conflict, any war and any sacrifice for that.

It’s also cynical in a way because of the way it emphasises this absurd situation – and the director Botond Nagy understands the significance of the text. He is able to create beautiful images on stage and very convincing emotional scenes but somehow he keeps the cynicism, even the sarcasm of the play’s metaphor. This makes it a production that is touching and powerful through the images and signals that it sends to the audience without being militant, a work of art first yet doesn’t let that stop it from offering a convincing observation on the reality that is around us.

NA: That reality is especially evident here because of the proximity of the border with Ukraine. You only have to look up Suceava on Google Maps and see that there’s a new refugee centre in the town. Plays like The Homecoming have a resonance here that an audience, say, in Germany and certainly the UK couldn’t feel.

CG: But I think that everybody can feel it, even if they are not so close to the war. The story of this play is significant for any family that has stories about their grandparents, their great-grandparents being in war – the First World War, the Second World War, any war – because if you have that connection with someone who suffered or was killed in a war, then you are sensitive to the idea of being killed for a cause that is not yours, that you are being used to be like cannon fodder.

During the performance, I was thinking about how the play’s message conveys this but on a different level, one that’s more cynical, more grotesque. And also more post-modern, for example like Fernando Arrabal’s Picnic on the Battlefield (Pique-nique en campagne), which has a similarly absurdist situation where a soldier, picnicking with his parents, is joined by an enemy soldier. They start to fight each other, see their human qualities and become friends, realising that both are victims of a system that is creating a conflict that is not their conflict. They don’t have to fight one against each other because they don’t have anything to compete about.

NA: Do you think that theatre is a good medium for the big issues of today because it can react quickly. You can’t make a film so quickly, a documentary is a different animal, and a TikTok is a TikTok…

CG: Theatre is a very good vehicle for creating empathy because it’s vivid, it’s direct, it’s not like seeing a film. Yes, you see a film at home or in a cinema where it is dark and you sit with other people, but in the theatre not only is there an audience but there are actors that are live on the stage. So there’s a powerful empathy with all the feelings, all the emotions, all the ability to agree or disagree with the situation you see on the stage, and that is something powerful.

Theatre is very much of the moment, a direct reaction which you cannot get in film or on TikTok. The notion of catharsis, for example, is used only in theatre. It’s not used in literature, cinema or the visual arts. It’s the only art that creates collective empathy, not personal empathy – it’s not a handful of individuals experiencing an inner feeling, but a group of people who experience the same feeling, all of them at the same time.

NA: Places like Germany have an impressive range of festivals, but few of them are pure theatre and there doesn’t seem to be a consistent depth to them. Here it seems that there’s a good range, depth and geographical spread of festivals aimed at pure theatre.

CG: Part of the reason is that we have a large network of public [= state] theatres – which is one good thing we have inherited from communism [laughs] – and we also have more than 80 publicly funded print magazines and journals. At the moment, we are still in good shape with the public’s support for culture, and though everything is shrinking and so on, there is still a strong base compared to other countries.

NA: Tell us more about the theatres.

CG: Our network of public theatres is mostly in the big cities but we have also a wide network of independent companies which are also financed through public support such as the National Cultural Fund. This is because access to sponsorship in Romania is hugely problematic due to bad legislation controlling this, and very few are able get this kind of support. So there is a sort of rivalry between the public and independent theatre networks which has created a tendency to find new ways of expression. For example, you’ll find a lot of documentary theatre from independent companies in Romania, reflecting the contemporary realities such as social and gender inequalities, racism, and it’s a genre that has been evolving over the last 15 years or so.

The public system was more rigid, more conservative, more traditional and more public focused, aimed at entertaining people more than educating or addressing issues. Over time this competition with the independent system has changed the public theatres’ way of working and this has influenced their younger audiences – the public theatres realised that they had to open up their repertoires and to integrate new ways of making theatre. So it’s not staging Shakespeare as it was staged 50 years ago or Chekhov in the style that existed 40 years ago. It’s about finding a new way of discourse – it can still be about Chekhov, Shakespeare, the classics, but it’s also about opening the canon to new techniques, new aesthetics, new themes.

I can see the results, but it’s hard to offer a specific explanation for the change. A younger audience is more open to a discourse that is straight-up or even brutal, which means that any dynamic audience will understand and welcome anything that seeks to take theatre into the future, that obliges the aesthetics to change and move on. These audiences are influencing that evolution of theatre in Romania.

Maybe that will lead to shorter shows with shorter texts, more images – but mainstream theatre here is already very visual and multimedia. So maybe in 20 years time we’ll have a kind of TikTok or Instagram theatre where you have a limited amount of words you are allowed to use to be understood and to reach the audience.

I believe we are seeing a turning point in theatre. Things were changing but extremely slowly over the last 15 years, but the Pandemic has made people change quicker and more deeply. Any new message will have to be doubled by a new aesthetic in the real meaning of ‘aesthetic’, but at the moment Romanian theatre is a melting pot. In 10–15 years we’ll see a new canon, a new way of doing theatre, and I believe that will be not only in Romania but all over Europe.

Daniela Șilindean

Critic at Orizont magazine, Timișoara

Web: Daniela Șilindean @ Research Gate

Nick Awde: Last night we saw Gogol’s The Government Inspector at the Matei Vișniec Theatre, staged by Moldova’s Satiricus Ion Luca Caragiale Theatre and directed by Alexandru Grecu. It makes the Inspector a lowly EU official arriving in Moldova from Brussels, in a production that’s a classic example of a trusted warhorse state theatre repertory piece: 20-strong cast, near-operatic blocking, tons of declaiming, the farce found more in the coding than the physicality, unashamedly playing to the gallery. But since I’m a Brit in Romania watching a production by Moldovans of a play in Romanian about the EU that was originally written in Russian by a Ukrainian from the Russian Empire, the question has to be less what was I watching, and more what was the rest of the audience watching?

Daniela Șilindean: It’s worth pointing out that there is a common background for the audience this show was designed for – the communist pasts of Romania and Moldova. This was exactly the audience that we had last night, and they were also responding to the shared stimuli of the contemporary political situation and real-life characters reflected in the play. There were tough nuances in the production – caricatures, grotesque – and of course people saw and understood that.

There is also the fact that here in Suceava the audience is one that has had only recently had regular access to theatre as an institution itself, so most see it as a cultural offer that comes to them and they dive into it. They accept it. And that’s a positive thing.

Certainly, that means there is a huge responsibility for the festival organisers to bring good cultural food to the audience. On the other hand, it is just as important for a festival to have different approaches and formats of shows. For an audience that has not been exposed to theatre of course you can feed them with the latest ground-breaking plays, but you also need to programme more accessible popular commercial shows that help to spread the word.

The audience last night reacted to the humour of The Government Inspector and it also reacted to the characters that were easy to anchor in a Romanian reality. The play’s theme of corruption and the appeal of authority has always been the norm – if there’s somebody you see today in a high position, that’s your authority as a reference. Then there are things like the nouveau riche who you find everywhere and are easily recognisable in our lives – that was definitely the big drive of the play last night.

It’s good to revisit texts like this. Needless to say, how you do it is something else. Maybe part of the plan was to say how do we get this play from the early nineteenth century on the stage today?

NA: And how to make institutionalised corruption relevant to all the European Union – it’s not just Eastern Europe.

Daniela Șilindean: Absolutely, corruption continues to be a topic not only in literature and fiction but in reality. People understand this and they get a good grasp of it, if it is presented on the stage.

NA: For the festival in general, how will you report on it? How will the Orizont readership be expecting you interpret and write about it?

DȘ: One significant thing for me is the fact that this festival stubbornly exists in a place that didn’t have a dedicated theatre until six years ago. That’s a recent change, fresh in the memory. And this is hugely important for the cohesion of the community here, a community that is not only still learning how to see theatre but also learning what to expect from theatre.

Exposing audiences to a variety of shows is healthy for the community. What’s also healthy is to have a theme like refreshing memory. What do you bring out of memory? How do you share it with other people? What’s your relationship with history? When you revisit history, you find uncomfortable topics, it can often be disturbing – and it’s essential not to avoid that too.

NA: So the festival is a mental extension of the physical theatre in Suceava.

DȘ: That’s true. Ignoring fashions or trends, we can evaluate the International Days shows through an aesthetic filter, but there’s an equally important aspect of the festival, which is building a community – literally building it. Not as an intellectual clique but as a reality. That’s tremendously necessary in terms of cultural work.

Coming back to memory and history, the opening show was The Homecoming, a play about war that Matei Vișniec wrote years ago. Seen within the context of today, the play’s trigger is even more powerful, like how do we talk about war? How do we refer to it? Do we even think about it, is it merely a reflection point? Is it yesterday’s news or today’s?

The production that we saw on the first night got us thinking by saying look at this, this is not a thing of the past. If we don’t revisit the past, we don’t understand anything from the present. And if we don’t understand anything from the present, then what are we doing here? So, theatre is also a powerful tool to give a punch in the stomach and bring things closer to the reality of today.

That is what I have in mind for my readers: memory, history, revisiting history.

NA: So for this week at least, here in Suceava, theatre represents something beyond entertainment and is actively reaching into our lives.

DȘ: Absolutely. Just look at how everybody talks about it here. We know this idea of memory on an intellectual level. But that’s not enough. For instance, there are people in Romania who have never thought about the crimes of the communist regime. But this is only 32 years ago, it’s not ancient history – it’s our recent history. But we don’t talk enough about it – and that’s crucial. So absolutely theatre here does have a different resonance.

Luana Popa & Dumitru Dinel Teodorescu

Photography, theatre, books, based in Suceava

Web: Un concept Luna

Nick Awde: A little bit about yourselves and your work…

Dinel Teodorescu: We are Un Concept Luna (‘A Moon Concept’), a non-profit entity from which we set out to familiarise people with the art of theatre.

The Matei Vișniec Theatre is seven years old now, the only new theatre in Romania to have opened after the December 1989 Revolution. It’s based in Suceava, a region that never had a local theatre company, and here the public can be shy about going to the theatre and also quite traditionalist and sceptical in accepting new forms of doing theatre. So, with that in mind, we established a number of projects that converge on the idea of bringing audiences closer to theatre.

There’s Teatru la Curte – Courtyard Theatre, a project for producing shows with one or two actors, suitable for open air, that we perform for private audiences in their own courtyards or gardens. The first performance is always free so people who don’t come to theatre for whatever reason, they can make an informed opinion whether they should then go or not got to a performance at the theatre. Some have discovered that theatre doesn’t necessarily hurt, while others after this garden/courtyard experience will of course say they tried but didn’t like it. It’s a great way of bringing theatre to people that don’t usually go to the theatre – those people have, usually, the loudest opinions of what theatre should be, what it should look like, etc.

We also do readings at schools – this is our dearest project and consists of bringing actors to schools to read theatre texts in front of kids in their classrooms. We have texts created specially for young audiences, gratefully put at our disposal by Lansman Editeur, a publisher in France, and the beautiful people who translate them from French and publish them for the Sibiu International Theatre Festival (FITS: Festivalul Internațional de Teatru Sibiu). Thus contemporary drama texts written for young audiences get to be read to their projected audiences by professional actors in schools all over the county of Suceava. To see kids exposed to this experience for the first time is the real deal.

With a specialist partner company, we present fire shows, usually at medieval festivals, and we also bring walls to life by installing photo exhibitions in business office buildings and medical facilities. The walls in these buildings can be cold and impersonal, and so a theatre photo hanging there won’t go unnoticed. Like the garden/courtyard theatre, there’s the idea of putting the spectacle right in front of people’s noses, at their workplace where they spend most of their day. Maybe if an image speaks enough…

And that gave us the idea of producing photo books. So far we have managed to publish three albums about rural life, fire and of course theatre.

As a result of doing that, we are now preparing the launch this summer [2022] of a cultural supplement in partnership with local newspaper Crai Nou, where we will cover contemporary art, theatre writing and poetry. It will be published every Tuesday instead of the sports section. Isn’t that a statement?

Luana Popa: So we’re just normal people who love theatre, photography, cinema, art in all its forms and varieties, trying to share with as many people as possible the things that make our life more meaningful and beautiful.

NA: What gave you the idea for the theatre photo book?

LP: We were lucky to be witnesses at the beginning of the theatrical adventure in Suceava in 2013 when Matei Vișniec together with a few people – among which I need to name the late Carmen Veronica Steiciuc, a poet who later became the theatre’s manager – started the International Days Festival. Every year since then, we have been a part of this event that unites the community. Then a dream came true when suddenly we had a theatre in Suceava and we realised that we were also building up a photo archive, a small but significant piece of history from the beginning of what has grown to be an important cultural institution – and it all began with a small theatre festival in a town that did not have a theatre.

We thought that it would be relevant and important to publish a book that brings together a selection of photographs taken during each festival as they mark a constantly important moment in the cultural life of the community and it also gives an insight into Matei’s works as interpreted by different directors, played by different actors and finally captured by us as photographers and spectators.

DT: We are in love with photography. So, after criticising a lot of photo albums for doing this or not doing that, and being aware that photography has become so popular that it is rapidly vulgarising itself, we made a bet with ourselves to see if we would be able to publish a photo album. Now that we are already on our third album, let’s see what their life will be like.

NA: Does the photographer have a special relationship with theatre?

LP: I think there is a special relationship, it’s one based on love and respect, attention to details, intuition. For me, theatre photography needs to tell a story, it needs to have feelings, capture emotions. It’s always a challenge – not to be intrusive, not to disturb, not to be seen, but see everything and capture it, wait for it to speak to your innermost self and try to push the button at the exact right time for that message to go through. Otherwise it’s just documentary photography.

DT: You can take great pictures of a lousy performance, and lousy photos of a theatre masterpiece. In these two arts, the peaks don’t always have converging points. You can always tell if the photographer had any chemistry with their subject, and Luana and I have fun spotting that. Without it, photography has no soul, as we like to call the moment when the photo speaks to you. Personally, I think that without loving theatre, or any other subject of the camera, the photos will turn out dead. It really shows.

NA: How does the book reflect the cultivation of culture in general in the Suceava region?

LP: The book shows photos from productions that have played on the stage in Suceava, by theatre companies from Romania but also from around the world, theatre companies that came to Suceava when there was no theatre and came back as guests of the municipal theatre afterwards. It shows continuity, it shows progress, and cultural variety. I think the book is also an opportunity to revisit our affective memory, to recall and relive some of the emotions and create the need to make new memories and live new emotions at the theatre. It’s also an invitation not to miss the experiences the theatre has in store for us all.

DT: We didn’t have the courage to edit a book until a known local photographer Sorin Onișor launched a call for someone to help him publish a photo album about old women from a rural world that will soon be history. That world of our grandmothers is already mere fiction for the millennial generation. So we responded that we’d do it and that was our first photo album – Rădăcini. Maicile neamului românesc (Roots: The Mothers of the Romanian Nation).

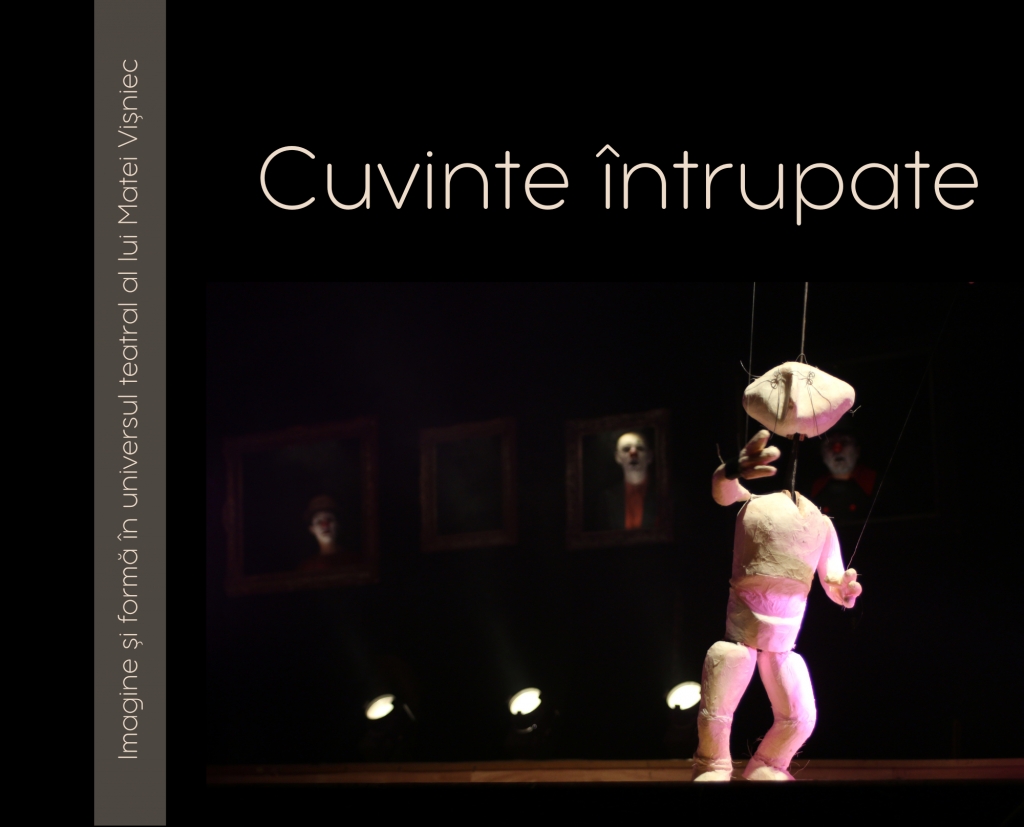

The second, Cuvinte întrupate (Embodied Words), is our dearest, as it is the living memory of years of the festival. There are photos from productions based on or inspired by Matei’s texts and performed over the years. In my opinion our book answers your question about cultivating culture on several levels. Aesthetically, as we tried to capture the beauty in the shows. Emotionally, as the many people who have been involved in the shows elate to them – as crew, actors or spectators, it’s evidence of the beauty that at some point passed through our town. And documentarily, as it depicts moments that have passed but, through these pictures, can be recalled – these pictures become, we hope, archives of feeling and the festival’s state of mind, a continuous hunger for beauty and ideas.

The project series title ‘Memoria afectivă’ – ‘The Affective Memory’, is extremely apt for its contents, these albums with glimpses of passed beauty.

NA: Is the Matei Vișniec Theatre an important addition to the cultural spectrum? What else is missing?

LP: On a local level it’s one of the most important cultural institutions and it provides important and relevant cultural content, which is also true at a national level. Through its cultural offers, the theatre is a pole of modernity, a converging point for arts, ideas, developing complex projects for the benefit of the community. It is only in its early years, and the beginnings are always challenging, especially funding, and while it takes time to create bonds with the national and international professional community, it is already on the right path.

DT: It’s a dream come true to have a permanent professional theatre in Suceava. Until its founding we didn’t have many other cultural events than traditional music events – usually folk, which are popular and a trademark of the county, so they were considered sufficient for a long time. The theatre provides and develops an infrastructure for all other cultural fields, no matter if it’s classical music, cinema or conferences, both with regard to hard assets like the building, stage, technical features or soft assets like the audiences it develops and their quality.

NA: Does the International Days festival represent more than theatre for you? For example, this year you and I, we all went to visit artists and monasteries. The politicians talked to Matei on the stage…

LP: Definitely a festival is more than theatre. Theatre is the main event, but all the encounters add to the experience. I think that all the energies around a festival are extremely important, the conferences, the debates, the planning, the projects, the people. The mood of the city changes. The festival is like a beacon of hope for the old projects and also for the new.

DT: The festival is an opportunity for all its participants. We have access to performances and artists that we wouldn’t probably otherwise see or have the opportunity to listen or talk to. And for the guests, as our county is welcoming in terms of heritage, landscape and, not least, food tourism, it can be a very fulfilling experience – both spiritually and literally.

Petru Hadârcă

Artistic director of the Mihai Eminescu National Theatre in Chișinau, Moldova

Web: Mihai Eminescu National Theatre

[Translated from Romanian by Nick Awde]

NA: You’ve brought two large-ensemble plays to the festival – How to Explain the History of Communism to Mental Patients (Istoria comunismului povestită pentru bolnavii mintal), written by Matei Vișniec and directed by Cristian Hadji-Culea, and Siberian Files (Dosarele Siberiei), written by you and Mariana Onceanu and you also directed. As a documentary drama about the Moldovans who were deported to the Soviet gulags in the 1940s, I know that Siberian Files is a very courageous work because it is only within the past few years that Moldova has started to fully confront its history of deportations and other atrocities caused by the Soviets. But was there a specific spark that made you embark on the journey to create something as ambitious as this?

PH: There were two circumstances that made me do this. The first and most powerful is the human factor, the personal effect on me from learning about the immense human suffering, tragedy and catastrophe experienced by each individual who was deported but also collectively by the people who have lived east of the Prut [the river forming the border between Moldova and Romania] after 1940 after the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, when our land was handed to the Soviet empire. The persecutions and methods of oppression of the communist regime, especially during the Stalinist period, were of unimaginable monstrosity.

As a director, I started working on the subject in 2009 when I was offered the chance to put on a radio documentary at Teatrul Național Radiofonic (National Radio Theatre) in Bucharest. It was based on the memoirs of the Romanian academic engineer Gleb Drăgan, whose story is symbolic of the people east of the Prut – in 1940, history separated him from his twin brother when he took refuge in Romania and his brother had to stay in the Republic of Moldova. Both had to hide the fact that they had relatives abroad, that they were brothers. I have been working on this topic ever since.

The second circumstance that led to Siberian Files was the fact that 2019 was the 70th anniversary of the second wave of deportations. It was the biggest, when 35,796 people were deported from Soviet Moldova to Siberia and the Far East – of whom 11,899 were children and 14,033 were women.

NA: What gap in memory of the Soviet past does the play fill for Moldova today?

PH: Knowledge of these facts and events was prohibited during the Soviet period, and many realities were distorted and interpreted diametrically backwards by the official history. The archives have been open since the 1990s.

As a personal example, I knew vaguely that some of my relatives had died of starvation, that my parents, as children, had escaped and were happy. But they didn’t speak about it. I did not know the extent of the events nor especially that it was a policy of the authorities and no one had told the story until the 1990s.

I had the feeling that I myself was also guilty of something, because I was a Pioneer and a Comsomolist [Komsomolets] and I had believed in what we were told at school, that “we were liberated by the Soviet Army, that in 1940 we were backward, without culture, without a developed economy, that we were illiterate”.

At the level of our collective mind there remains both a great emptiness and a great confusion – there has been no acceptance, no awareness of the crimes orchestrated by the communist regime as has happened with those of fascism.

NA: Though based in Romania, the International Days Festival must have extra importance for you because Suceava is right on the border with Moldova – and also with Ukraine.

PH: The festival has become a key event in our cultural calendar, and I need to point out that Matei Vişniec enjoys enormous respect and admiration in Romania as a man of culture, through his poetry, his novels and his plays, which are produced on stages in so many countries – and that is why he connects as a journalist and broadcaster, as an opinion-maker you can trust.

That’s an extraordinary thing – and an important one, especially today when peace and stability in our world have become so fragile. After two years of pandemic and the sudden war that is taking place in a country that we share our borders with, in Moldova we have come to feel acutely aware of the price of freedom and peace.

We have constantly lived under the threat that our freedom is endangered and we risk losing it again, as happened in 1940. That is why we live with great intensity every moment of freedom we still have.

Ukraine’s Chernivtsi Drama Theatre and playwright Neda Nejdana also participated in the festival, and this reminds us that artists in Ukraine are at war, where not only young soldiers but also children, the elderly, women die every day. It is a war between two worlds: one that believes in dictatorship and order imposed with an iron fist, and one that believes in the world of democracy and freedom.

Along with Siberian Files, the Mihai Eminescu Theatre has also brought to the festival our new production of Matei’s play How to Explain the History of Communism to Mental Patients – we first staged it in 2021 with director Cristian Hadji-Culea, who is also artistic director of the National Theatre of Iași [the biggest city in northeast Romania].

NA: How has the reaction to Siberian Files in Moldova been? Is it all positive, or is there resistance to it?

PH: There are still influential groups in the Republic of Moldova that support the Soviet Stalinist communist policy and who want to return and rebuild the old Russian-Soviet empire. Unfortunately they have a strong political influence throughout the political parties and high-ranking officials in the state.

This explains why for 30 years of independence, i.e. from 1991 right up to 2019, the subjects of political persecution, deportations, hunger and the gulags were not represented on the stage of our professional theatres – and yet in Chișinău we have three national theatres and several independent ones.

You asked me why I came to produce this material now. I have been working on the subject since 2009 – but the fact is that I was doing it on Romanian territory. In the Republic of Moldova I did not have the possibility because I was banned during the long period of censorship imposed by the then communist regime of 2001-2009.

So I need to give a third circumstance for why this is happening now. As a producer I knew I needed to take responsibility as an individual to create a play like Siberian Files, and so, from the moment I was appointed artistic director of one of Moldova’s cultural institutions in autumn 2013, I made the decision that subjects connected to the awareness of our past need to be part of any policy that shapes the Mihai Eminescu Theatre’s repertory.

The first production to address the subject premiered on May 27, 2014. This is Children of Hunger: Testimonies (Copiii foametei. Mărturii), a documentary theatre piece adapted from the book In the Mouth of Hunger (În gura foametei) by [Moldovan-born writer] Alexei Vakulovski, dramatised and directed by Luminița Ţîcu. The play is about the famine organised by the communists in 1946-47 as a method of coercion, fear and subordination of the people of Moldova, using the methods used earlier against Ukraine 1932-33.

As I answer these questions, we hear the alarming news that the Russian Federation is now attacking grain stores in Ukraine, blocking grain exports, and the risks of a global food crisis are growing. It seems that the political engineers who once worked in the territory of the Soviet empire are being redeployed on a larger scale, right?

I can’t help but wonder that if the Western world had the time and inclination to pay attention to the experiences of Ukrainians in 1932-33 and the Romanians in eastern Moldova on the Prut in 1946-47 when they were starving, if the West wanted to learn what was happening, could we have avoided this catastrophe?

I’ve heard from Russian sources how their political commentators deny those realities. Just as there are voices in Chișinău who accuse me of using the theatre of Siberian Files and History of Communism as pro-Western and pro-American propaganda.

So if we are speaking about history, we are repeating it. In 1937 in Ukraine and in the Autonomous Socialist Republic of Moldova, east of the Dniester, Stalin launched the Great Terror, the campaign to purge the ‘nationalists’ from Soviet life. I don’t think we have learned our lessons, especially our history lessons – and this is why I insist on putting these subjects on the stage, at least where I have the power to speak about them.

NA: Is theatre a good way to communicate difficult subjects like the horrors of deportation?

PH: Theatre does not have anything like the influential reach of the internet and yet our shows have a huge impact on people that we could never have predicted. When working on Siberian Files, we were particularly afraid that it would not be the type of show that would attract audiences, we thought people would actively avoid coming to see a show about something so complex.

But to our surprise, the shows always sell out. People come because of the magnitude of the catastrophe that has affected so many thousands of people and marked their descendants. It convinced me once again of the emotional power of art, and theatre in particular. Once again we witness the power of catharsis that can only be triggered in a theatre, only in a live show – when actors and spectators breathe, laugh and cry in the same space.

We have discovered that around two-thirds of our audience is made up of young people as well as the active [working] adult population – civil servants, doctors, teachers, entrepreneurs, many of them descendants of deported families. There are people at every performance who are eyewitnesses or victim-eyewitnesses, people who have the experience of being classified as ‘enemies of the people’. Usually after the show, many of them come up and talk to the creatives and actors, asking for their stories to be heard or the stories of their family.

Sometimes a particular emotional state can be triggered during the performance. This happens especially when there are victim-eyewitnesses in the audience of the stories retold in the show. They are few in number, elderly people who often come on crutches, accompanied by relatives.

The relatives warn us they are worried that these people will not be able to control their emotional response. Their entrance into the hall, of course, attracts attention. Towards the end of the first part of the play, when the dramatic tension builds, in the silence there you start to hear sobs, involuntary weeping. There is a connection that is hard to describe, it is like a nod, a confirmation of the fact that what is happening on stage was real – is real – and the real characters who suffered are still among us. This presence amplifies the emotional impact of the play.

It is also interesting to see the reaction from the younger generation. They usually come in noisily, busy on their phones, making jokes and chatting amongst themselves. At the beginning of the show they are looking at their phones, then gradually the lights of the phones go out. Towards the end, the hall is immersed in deep silence, their focus to the stage is maximum.

It seems that through this show we have achieved a level that we had not set ourselves, where I think a kind of group therapy is created. Only now do I understand how the suffering of the people who went through those horrors was doubled because it was amplified by the fact that in the Soviet period they were forbidden to speak about it, to mourn their pain – they were forbidden to mourn.

The direct physical suffering ended in 1956, but the mental suffering did not go away due to the fact that they were not allowed to mourn their pain, to share it with others. After 1990, books were gradually published and academic symposia were held on the subjects, but books are read in solitude and academia is cold and statistical, limited to a small circle of people. In the show’s programme there is a list of victims which I have entitled ‘Cifrele au suflet – Numbers have a soul’.

The play seems to give the survivors of those times the opportunity to mourn their grief in public, where their children and grandchildren can empathise with the fate of their grandparents, and it seems that it generates an emotional closeness for everyone there. When we developed the project we did not think about this phenomenon. But it really does happen during the performances.

Other plays have impacts in other ways, especially now that there is the war in Ukraine and the imminent threat of the establishment of a dictatorship. This has changed the public’s perception of Matei’s History of Communism, which we have also brought to this year’s festival. Until the war, the scenes in this particular play were treated with humour, their situation seemed so absurd. Since the military invasion began, no one is laughing, the danger of the return to this nightmare is so real that the world hears and interprets the text differently.

What we did not think was possible in this century happened, the barbaric invasion of democracy and freedom, but come and see How to Explain the History of Communism to Mental Patients and everything will be clear.

NA: Gulag survivor Margareta Cemârtan-Spânu was present in Suceava for the performance of Siberian Files. What has been her link in the play’s development?

PH: Margareta is one of the most energetic voices to speak out about the deportations, a witness who works constantly to make the experience of her generation known. Her book about her experiences, Lupii (Wolves), is one of the main sources that Siberian Files is based on.

Initially I thought I would just stop at her material and have a show that was shorter in duration – you know, all the doubts about today’s audiences being more hurried, wanting less text, more compact staging, and so my original directorial concept was different. But after reading a lot of other testimonials I decided to change the concept and I chose two other documentary sources to adapt.

So Margareta represents the voice and perspective of the deported children – she was deported at the age of six – in the second wave of deportations in 1949. The voice of the deported adults is represented by the memories of Ecaterinei Chele, a teacher who was deported with her baby in the first wave of 1941. The third voice is based on the documentary source of the memoirs of political prisoner Ion Moraru, who in 1950, when he was 21 years old, was sentenced to ten years in a labour camp gulag, another ten years in exile in the far reaches of the Far East and five years ‘suspension of civil rights’ – a total of 25 years in prison. In 2019, when we premiered the show, he was still alive, he was 90 years old.

NA: Outside of Moldova, how have the audience responses to Siberian Files been?

PH: The response depends on the audience we play for. If we talk about Suceava, Rădăuți [both in northeast Romania] or Chernivtsi [southwest Ukraine] where we played in 2019, then the response has been the same as in Chișinău, because the people there have gone through the same experiences. We have performed the show in Bucharest on the main stage of the Ion Luca Caragiale National Theatre, at the Sibiu International Theatre Festival and in Budapest on the stage of the National Theatre there.

So many people are shocked to discover this past and many say that it has made them understand why people in Eastern Europe have this psychological profile, because of the traumas that have so deeply marked their level of collective consciousness.

So yes, Matei’s theme of ‘Refreshing Memory’ is a universal theme that resonates deeply with our fears and worries, and I think it is a call to reason, for us all to learn something from history and not to repeat it.

Răzvan Bănuț

Actor at the Matei Vișniec Theatre, Suceava

Web: Răzvan Bănuț @ Matei Vișniec Theatre

Nick Awde: The ensemble of the Matei Vișniec Theatre opened the International Days Festival with a new Romanian-language version of Matei’s The Homecoming (Întoarcerea acasă/Le retour à la maison). Tell me about the play…

Răzvan Bănuț: Just looking at the script gave us the feeling that it was going to be a rather challenging and unusual type of project. Matei Vișniec’s text is interesting because it’s not a normal plot in which you have the evolution of characters and the road they’re taking, all the obstacles that they have to overcome. It’s a series of monologues that, in a way, create a multiple character – each piece of text comes not from just one individual but from a group of people who choose a representative to go talk to the General about their concerns and demands. Also, the entire conversation takes place after the soldiers’ deaths. They’re all trying to convince the General that they should be put first in line to proudly enter the capital.

Despite the fact that the text was so rich in details and absurd yet hilarious situations, we had a rather difficult time finding ways to transfer it onstage. That is because you usually have a storyline that leads you to something, but it wasn’t the case here. The characters being all dead means that the conflict is also cold and a bit dead. So the challenge was the staging. How do you liven up an atmosphere where nothing seems to change, where everybody seems to talk, but nobody takes action?

Enter our director, Botond Nagy. He didn’t settle until he found the perfect images, the best ways to depict the energy he felt was behind the text. It was exciting working with him again. We’ve worked with him before and we know the direction he goes in, the style he approaches in his work. We also discussed with Matei, who said that we could create something new with his text – he always wants his texts to be transformed – and in his own words he said he wanted us to “rip apart” the traditional script word by word.

NA: Having already read the script previously, I agree that it’s ‘flat’ in terms of action, plus it’s not very long. It was an interesting surprise to see how Botond and you the ensemble have come up with a two hours, ten minute play, which is perfectly paced and finds that depth not only text-wise but also in the starkly beautiful design.

RB: We talked about the play with Botond, and he pretty much let us rip the text apart and have fun with it. We took each monologue and created something playful out of it. After a process of many trials and errors, Botond took our suggestions, came up with his own ideas and, almost unnoticeably, everything just fit into place, everything. The characters, the stage design, the lights, every piece of the puzzle seemed to have found its spot, creating this amazing final image that is our show.

NA: The final result plays very much on the visuals of ranks of soldiers, and the dialogue effectively plays off that.

RB: The lighting is brilliant, yes, because each change of light gives you another space, another atmosphere, another energy, thus creating various and unique feelings for the audience.

NA: How do the actors and the creatives see the play’s themes in terms of relevance to Ukraine?

RB: I talked about this with the director because I had to acknowledge that I don’t really know anything about war. Yes, I have read a lot about it – especially now with this war that is going on in neighbouring Ukraine – but I didn’t actually know anything about the reality. Of course I can theorise about war but I don’t know what it’s like to have a bomb falling five feet from you. So it was an important subject that I had to discuss with Botond. I began working on the project and on my characters from the point of acknowledging that I had no idea what being in a war was actually like.

What happens to these soldiers after death? Is it important to continue as a soldier after death? Is it important to continue the struggles of the war, the need to be acknowledged as the first soldier in the parade or the last soldier, or as a general or any of the other ranks?

Discussing all this with Botond made the actors realise that we can use these ideas but only as guidelines – beneath all that, we had to approach the ordinary behaviour and reactions of any human being. Mainly, there is always this need to be the first to win something, the first to get somewhere – and you are angry when you lose or don’t get what you want. We don’t have to be soldiers in a war to understand this desire to win, to be acknowledged, to be rewarded.

NA: You must have a good system for working because you are an ensemble permanently based at the theatre. Are you all from Suceava?

RB: No. I’m from Zalău, it’s a small town in the northwest of the country. I went to study theatre in Cluj-Napoca and graduated in 2012. From that point, I travelled through the country and then worked at the theatre in Piatra Neamț for four years. After that I came to Suceava and I’ve been performing here since 2017. Four of the other team members are from Suceava and the rest of us are from Iași, Paşcani, Brăila, Zalău – so when we first met, we were very different. But now after all these years, we have come to know each other and create a real team.

NA: Tell us a bit how the national [ = state] system works to employ people in the theatre industry.

RB: I don’t know if this if this is a system left by the communist era, but it is a national system where most actors look for work in an institution. You audition, you get hired, you work and, in some places, you get a permanent contract. In other places, like in our case, you get a one-year contract or one for six months, for example. After this period, they either renew it or they let you go.

NA: If you stay in a theatre for longer than a year, how does it work? Do they promote you to something like ‘Senior Actor’?

RB: Yes, there are different ranks you can achieve. You get promoted to a higher position based on your age, the amount of time you spent on stage and based on the experience you’ve gathered whilst working in the theatre.

NA: It must an interesting experience to work at the Matei Vișniec Theatre because there aren’t any other theatres nearby.

RB: That’s true – the nearest is in Botosani, approximately 40 kilometres away. Not only this, but our theatre is also a young one. It initiated its activity 6 years ago. Until then, our town didn’t have a theatre for almost 40 years.

NA: Does the ensemble feel that what you are doing here matters, because the audience here potentially only has you, unless they want to go a hundred kilometres to see another show?

RB: Of course. We’re the first actors who got to be part of this ensemble so it gives us a great feeling of responsability towards our audience. We carefully pick the plays we want to stage because we are aware that our public has different needs and so do we, as actors. We want to evolve together, both us and our audience. We also have a great responsibility towards our team. We are indeed very different, but we managed to blend in our energies and our potential to create a rather solid and compact artistic group.

NA: I can see that, if only from the evident teamwork in the play.

RB: It is an interesting mix because we’ve all studied at different theatre schools [with different techniques] so we had to adapt to one another. In Romania there are various Drama schools, each with its unique technique. Unfortunately, when students graduate, they have a hard time finding a place to perform. Therefore, over the last 20 years or so, independent companies have started to emerge but here in Romania it’s hard for an independent company to survive.

Here at the Matei Visniec Theatre we are only ten actors, as opposed to the rest of the theatres which normally hire at least twenty. So we are a rather small team but with diverse resources, skills and, since we are all very young, plenty of energy. This attracts a lot of relevant and creative directors who always challenge us to improve and discover new ways of expressing ourselves on stage.

It’s a constant work of adapting. Sometimes it can be rough but in the end it’s always rewarding. I think these struggles help us evolve and lead us to a better understanding of our profession.

Matei Vișniec – Two

Playwright

Web: www.teatrulmateivisniec.ro/en/ | www.visniec.com/home.html

[Translated from French by Nick Awde]

Nick Awde: What was the festival like when it first started, when there was no theatre building in Suceava?

Matei Vișniec: I started the festival with a few friends and we found the funds to make the productions free, and people came to see them in different spaces. One was the House of Syndicates – it’s a huge space with 800 seats and it was full. After four years of doing it like this, Suceava’s political authorities decided to invest money in a true theatre – a former cinema which they wanted to renovate.

The town’s mayor Ion Lungu is a liberal, if you want to see his political colour, and he has a lot of common sense – and he told me that the city wanted to create a municipal theatre with actors who would be invited to live and work in the town. But, he added, they needed my name on the front of the theatre, so could I help? In some ways, it’s not such a strange thing to ask.

NA: At the very least he’s thinking branding and PR – which isn’t always a bad thing.

MV: Of course, and he is also thinking ‘modern’. So I said, yes I can help. But I also wrote him a letter in which I put all my ideas for setting up the theatre. I said, yes I am willing, I accept… But I also said, look, what I understand by theatre is its independence. We don’t want a political person to come to say, “You have to stage this playwright, you have to bring that director.” I need an institution with liberty, like the press, which is a sort of ‘counterpower to the state’.

The press needs to be free to be able to serve democracy, justice must be independent to be able to play its role in democracy, and culture must also be independent to be able to play its role in democracy. I want an independent theatre, and little by little I want people to come to the theatre after walking in front of the theatre and seeing my name up there – and when they say my name, I want them to think to understand that behind my name there are values. This is a guy who is a democratic person, somebody who fights for democracy, for liberty, for the letter of the law, for the independence of culture in Europe, I’m pro-European for education.

So that’s what I told him, the theatre was opened, and little by little people are understanding that in this theatre we produce culture that is independent.

NA: And the Matei Vișniec Theatre, under managers Carmen Veronica Steiciuc and now Angela Zarojanu and the great team working there, seems to have achieved a huge amount in just six years.

MV: Yes. We have produced interesting plays directed by young directors from Romania and abroad who are talented but at the same time courageous because they offer new approaches to the 10 actors in the ensemble.

They also offer new connections – for example, we want to produce Ionescu’s Rhinoceros and we have asked a French director to come to direct it. That’s Alain Timár, and because he has a theatre in Avignon, we also have the idea that we can take the play to the Off next summer there [2023].

In the six years since it opened, the theatre has built up a diversity of plays in its repertory, including a Shakespeare, a Chekhov and two of my own plays. I think people in Suceava have understood something that’s very important for me, that this theatre is a special place for them and for the children, the young people here. We are lucky because Suceava has a university, which means that we have a lot of students around.

The people here support us and they understood what the theatre means because it offers something to the young people that isn’t sports or Facebook. They can come to the theatre to build their critical spirit. And we shouldn’t forget the many people from outside the Suceava region who have also supported the growth of this project – the journalists, artists and theatre companies.

The theatre is significant because we never had modernity in this part of Romania. We had tradition, history, a medieval festival, but never a theatre like today. I hope it will be a lasting institution.

The festival of course now takes place at the theatre and each year we try to to invite people from abroad. For example, this year we have a play from France – Ce silence entre nous (This Silence Between Us – written by Mihaela Michailov, produced by Poitier’s Compagnie Veilleur).

Of course it’s a small festival in a small city, but I have seen that it is also making a transformation here, adding to the theatre’s effect. People are noticing, for example they are starting to be proud of their theatre actors living here. They’re already stars because the young people have seen them so many times on stage!

NA: Alongside the plays, the festival has always featured talks and debates that tackle issues that are important to society across the world. Does this mean that theatre is an effective forum for change?

MV: Of course. In fact the theatre here in Suceava has created a new Romanian-language production of my play The Homecoming (Întoarcerea acasă/Le retour à la maison), where the actors of the theatre’s ensemble worked with the talented young director Botond Nagy.

The play’s title is slightly misleading because those who are ‘coming home’ are in fact the dead soldiers of an imaginary ‘homeland’ that represents all homelands. It’s a play that I wrote 15 years ago to denounce the absurdity of war in general, while I also talk about the contradictions of human beings.

In the play, the General, who is also dead, announces to all the dead soldiers that mass forgiveness and eternal peace have been ‘decreed’ — although we never know by whom — and so the dead soldiers can finally return home to their families. The General starts planning a military parade for a celebratory entry into the capital, but its organisation turns out to be anything but simple because the dead soldiers begin to fight for the right to be at the head of the column.

My play may be a grotesque comedy, but the reality of the war in Ukraine, with its macabre and absurd aspect, goes far beyond fiction. Therefore remembering that the great tragedies of humanity have often been triggered by absurd spirals is very important for me.

During the festival, the invited artists did workshops and talks in high schools in Suceava because ‘transmission of memory’ is also an important part of what we do. Theatre has the capacity to contribute to our need for transmission because in the history textbooks there are chapters that are incomplete or simply black holes. I often have to point out that no trial – at least a moral trial – of communism has ever been carried out in Europe as it was done with Nazism. This explains the fact that an ideology which is responsible for the death of a hundred million people still holds a certain attraction.

For anyone wanting to understand the murderous nature of communism, I recommend that they should read the World History of Communism [Histoire mondiale du communisme] by French historian Thierry Wolton. It is in three volumes entitled The Executioners, The Victims, The Accomplices. Among the ‘accomplices’ are the many Western intellectuals who, through their blindness and lack of critical courage, endorsed the crimes of Stalin, Mao, Pol Pot…

NA: What made you choose Refreshing Memory (Reîmprospătarea Memoriei) as this year’s theme? Was it a response to the war in Ukraine?

MV: I actually suggested ‘Refreshing Memory’ to the theatre as a theme for the festival long before Russia’s attack on Ukraine.

I have already been writing articles for years on the danger of forgetting the errors of the past. Before February 24, 2022, it was clear to me that the European Union was in a sleepwalking state, preoccupied more with economic issues than the defence of democracy. Over the last decade we have watched democracy decline all over the world. It is rapidly declining in Asia and Africa, and even in countries in Central and Eastern Europe where corrupt political forces are busy emptying democracy of its content. It has almost become a specialty in some countries which do not have a long tradition of democracy — they adopt the form but change the content.

Over the same period I have also observed how freedom of the press in Russia has been annihilated by Putin and how the cult of Stalin has been rehabilitated.

NA: It’s clear that memory has a very different resonance for the former communist countries of Eastern Europe than it does for those of Western Europe. How do you see this difference manifested today?

I think the European Union has been blind in accepting such a major energy dependency on Russia as well as outsourcing parts of its industries to places like China. The theory that the intensification of world trade and exchange would advance democracy throughout the world has turned out to be completely false.

And then we can see that the consumer society has not been the best ally for democracy. There are serious abuses in our so-called ‘consumer’ societies which impose mechanisms to transform the citizen — i.e. someone who thinks for themself and keeps their critical spirit — into an obedient consumer who does not think any more and who instead becomes guided by the urge to possess material things.

These are just a few of the reasons why I suggested the theme of refreshing memories, so we can remember together the essential values that have served as the basis for European reconstruction.

After the First World War we said: “Never again! We must build a world where war can no longer be used as a way of resolving disputes.” And then we had World War II.

After 1945 we said – in Europe at any rate – the same thing: “Never again!” And we had the war in Bosnia between 1992 and 1996, a war that ended with 100,000 dead.

And now we have the war in Ukraine.

Why is war returning to Europe like a poisoned comet, why are toxic ideologies rising from their ashes? These are questions that I want us to address during the festival in Suceava, a town of 100,000 inhabitants located just 40 kilometres from the border with Ukraine.

I also want us to talk about the mission of artists, so we can talk about this question of what can artists do against barbarism? This is why this year I asked the festival to invite the Ukrainian writer Neda Nejdana to Suceava, the author of several remarkable plays about the Revolution in Maidan Square in 2014 [presently working out of the Chernivtsi Drama Theatre].

NA: Moldova brought three large-scale productions to the festival from two of its national theatres – including a version by the Mihai Eminescu National Theatre of your play How to Explain the History of Communism to Mental Patients. That’s an important connection, isn’t it?

MV: I wanted Moldova to be here because the country is also targeted by Moscow’s expansionist policy. In Moldova there is a strong Russian community which can be manipulated by Putin to destabilise the country, while the easternmost part of Moldova, Transnistria, seceded after the fall of communism and has been used since then by Russia as a base for its military.

The Moldovans are afraid at the moment, afraid of losing their independence and of being ‘punished’ by Putin because of their desire to approach Romania and the European Union.

Siberian Files (Dosarele Siberiei) is a play brought to the festival by the Mihai Eminescu Theatre which takes as its subject the deportations carried out by the Soviets in Moldova during the 1950s. Stalin ordered the deportation of peoples at many times across the USSR, and the Moldovans were not spared. At the moment, the Ukrainians in the regions occupied by the Russian forces are suffering the same fate.

In Russia today people do not even have the right to use the word ‘war’ to describe what is taking place in Ukraine. So something toxic, tragic, revolting is being repeated in the history of Europe and of humanity in general. I find this frustrating – of course this is the result of a collective failure of humanity but also of the West’s lack of vigilance.

NA: So ‘Refreshing Memory’ also means…

MV: …that democracy’s power of fascination is diminishing now, because many people, including young people, are attracted by extremist agendas. If one day by chance, stupidity or inattention we lose our freedoms, our awakening will be painful and it will take enormous sacrifices to return ourselves to being free.